You may be wondering why I jumped into this study of poetic forms with Asian forms (sijo, renga, tanka) and DIDN'T start with haiku. Honestly, it's because I think haiku are really hard to write. Seems ridiculous, doesn't it? But if you follow the rules (and there are lots of them), writing haiku in the spirit intended requires patience, a keen eye, and skill.

Here is the formal definition of haiku and some notes about the form provided by the Haiku Society of America.

Here is the formal definition of haiku and some notes about the form provided by the Haiku Society of America.

A haiku is a short poem that uses imagistic language to convey the essence of an experience of nature or the season intuitively linked to the human condition.

Most haiku in English consist of three unrhymed lines of seventeen or fewer syllables, with the middle line longest, though today's poets use a variety of line lengths and arrangements. In Japanese a typical haiku has seventeen "sounds" (on) arranged five, seven, and five. (Some translators of Japanese poetry have noted that about twelve syllables in English approximates the duration of seventeen Japanese on.) Traditional Japanese haiku include a "season word" (kigo), a word or phrase that helps identify the season of the experience recorded in the poem, and a "cutting word" (kireji), a sort of spoken punctuation that marks a pause or gives emphasis to one part of the poem. In English, season words are sometimes omitted, but the original focus on experience captured in clear images continues. The most common technique is juxtaposing two images or ideas (Japanese rensô). Punctuation, space, a line-break, or a grammatical break may substitute for a cutting word. Most haiku have no titles, and metaphors and similes are commonly avoided. (Haiku do sometimes have brief prefatory notes, usually specifying the setting or similar facts; metaphors and similes in the simple sense of these terms do sometimes occur, but not frequently.

I have heard it said that haiku is not a form, but a way of experiencing the world. Like all good poetry, haiku is based on close observation. This is summed up particularly well by J. Patrick Lewis in the introduction to Black Swan/White Crow, where he describes the form and encourages readers to write their own haiku.

To write a haiku, you might go for a walk in a city park, a meadow, the zoo. Put all your senses on full alert. Watch. Listen. Imagine that what you are seeing or smelling or hearing has never been seen, smelled, or heard before--and may never be again. Now take a picture of it--but only with your words.

The best haiku make you think and wonder for a lot longer than it takes to say them.

There are many, many rules and guidelines for writing haiku. For those serious about following in the Japanese tradition, the Shadow Poetry pages are very helpful. I also recommend reading a 2009 post by Diane Mayr of Random Noodling in which she shared a thoughtful note from Michael J. Rosen with his views on haiku. It is an interesting and provocative conversation entitled What is Haiku? And Who Decides on the Definition? that will definitely get you thinking.

There is a wide selection of books written in haiku for kids. I would recommend starting with one of these books that includes and/or uses classic haiku by Japanese masters.

Today and Today (2007, OP), is a collection of selected haiku by Kobayashi Issa that are paired with the illustrations G. Brian Karas. Woven together they tell the poignant story of a family over the course of a year. Divided into seasons, the collection opens in the spring. Here are two poems from the first two seasons in the book.

Once snow have melted,

the village soon overflows

with friendly children.

So many breezes

wander through my summer room:

Here's what Karas says about his work.

In my artwork, I have tried to achieve visually what Issa achieves with words, to convey the precise feeling of each moment so that someone else might feel it, too. The buzz of a hot summer day or big wet snowflakes hitting your face—it is ordinary, extraordinary moments like these, strung together, that make up our lives.

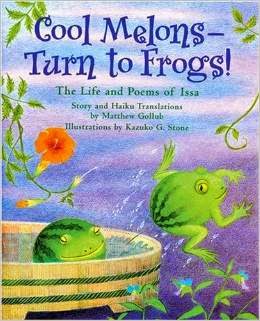

Cool Melons—Turn to Frogs: The Life and Poems of Issa (2013), written by Matthew Golub and illustrated by Kazuko G. Stone, is a biography and introduction to the work of Issa, the Japanese haiku poet who wrote more than 20,000 haiku over the course of his life. The work of Issa is interspersed throughout the narrative about his life. While not presented in the chronology they were actually written in, they are rooted in Issa's experiences and nicely complement that story. Each of the poems featured is rendered in Japanese in the outer page margins. Back matter includes information about the book's creation, transliterations and translations of the poems, haiku, and more. Here are two of Issa's poems featured in the book.

Plum tree in bloom—

a cat's silhouette

upon the paper screen.

A kitten

stamps on falling leaves,

holds them to the ground.

Overall, this is a very nice introduction to Issa and the art of haiku.

Wabi Sabi (2008), written by Mark Reibstein and illustrated by Ed Young, is the story of a cat named Wabi Sabi, who goes on a quest to discover the meaning of her name. (Wabi sabi is a Japanese philosophy and aesthetic that finds "beauty and harmony in what is simple, imperfect, natural, modest, and mysterious.") She asks many different creatures along the way, but they all answer in essentially the same way, telling her that it is a difficult concept to explain. However, each one offers her a little insight in the form of a haiku. By the end of the story, after reflecting on drinking tea with a wise monkey, Wabi Sabi has reached an understanding of her name's meaning.

Reibstein uses three different strands of text. First there is a prose narrative that tells Wabi Sabi's story. There is also the haiku that concludes each of the interactions. Here are two examples.

Finally, on each spread there is another haiku, rendered in Japanese characters. The translations for these appear in the end notes. These haiku are all classics written by Basho and Shiki.

The carefully crafted narrative, beautiful haiku, and stunning artwork will lead readers to an understanding of wabi sabi just as the cat is learning the meaning of her name. Readers will also find the fact that the book reads like a scroll (from top to bottom) an interesting feature.

Reibstein uses three different strands of text. First there is a prose narrative that tells Wabi Sabi's story. There is also the haiku that concludes each of the interactions. Here are two examples.

An old straw mat, rough

on cat 's paws, pricks and tickles...

hurts and feels good, too.

The pale moon resting

on foggy water. Hear that

splash? A frog’s jumped in.

Poems ©Mark Reibstein , 2008. All rights reserved.

Finally, on each spread there is another haiku, rendered in Japanese characters. The translations for these appear in the end notes. These haiku are all classics written by Basho and Shiki.

The carefully crafted narrative, beautiful haiku, and stunning artwork will lead readers to an understanding of wabi sabi just as the cat is learning the meaning of her name. Readers will also find the fact that the book reads like a scroll (from top to bottom) an interesting feature.

Don't miss the Educator's Guide for Wabi Sabi, or this video about its creation.

It's true that haiku is more than a form. Haiku moments are real experiences, not syllable counts. Without a real haiku moment experienced by the author, there is no haiku. It is a moment of heightened awareness.

ReplyDelete